Our authenticity-obsessed culture turns real people into entertainment, but it’s just another layer of performance.

In the early days of internet fame, the world was run by characters. MirandaSings, Fred, even Shane Dawson’s early content — in the late 2000s and early 2010s, being famous online generally meant playing a role or providing a distinct service (skits, product reviews, parodies, reporting the news). The audience knew that these characters weren’t real; the people they watched on their YouTube screens were actors playing parts, and the divide between person and persona was relatively tangible.

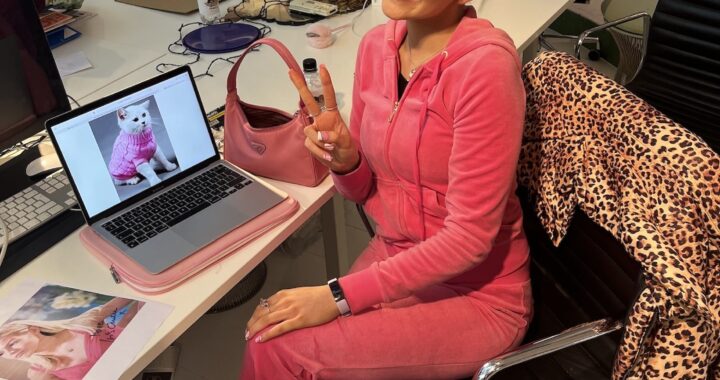

Somewhere in the 2010s, though, the creator economy shifted. Suddenly, the prototypical influencer was one who could craft a window into their real life, supposedly as unfiltered as possible — authenticity became the brand, and creators like Emma Chamberlain were the gold standard for selling it. And it’s not just an influencer thing: consumer interests at large have shifted to prefer the facade of authenticity over an obvious performance. Now, algorithms push skincare over makeup; messy, grimy “indie sleaze” over the “clean girl aesthetic”; seemingly nonchalant photodumps over ringlight selfies. Performance is out (at least in its most obvious sense), but it’s also more necessary than ever before; the catch with all of these industrial shifts, of course, is that one must still be obviously perfect in all the ways that matter in order for their “authenticity” to be deemed worthy of consumption.

Because perfection (whether physical, moral, or otherwise) is essentially defined by its inaccessibility, authenticity doesn’t actually require any less construction than the modes of entertainment that came before it. It’s not that creators have stopped playing characters; it’s more like the modern consumer, now jaded from growing up in a hyper-commercialised online world, has begun to demand a more immersive and masterful performance than ever before. Now, the creator must sell a fictionalised version of themselves that is impossibly charismatic, tastefully self-deprecating, messy but never ugly, unfiltered without ever crossing a line — and they must insist that this person is real, no matter how impossible we all know that to be. The new model of fame aims to blur the line between performer and character until nobody (sometimes not even the creators in question) can tell the difference.

It’s common to see influencers on TikTok openly brand themselves as stand-in big sisters, best friends, and parents (“It’s me, your online bestie!” has become a popular way for young women to open their lifestyle vlogs). Professional personalities like the Try Guys’ Ned Fulmer transparently build personas carefully calibrated to meet consumer demand. And in a world where young people’s lives are increasingly isolated and chaotic, it seems natural that consumers would want improbably perfect pseudo-besties, devoid of real complexity or moral impurity.

But as the Try Guys have discovered, this parasociality-on-steroids often backfires in a big way on the creators that foster it — when you’ve built a profitable brand on being a sister-figure, a loving husband, or an indisputably good person, even run-of-the-mill personal failure becomes an existential threat to your career. And while creators have a responsibility to manage their platforms ethically, consumers should engage with a more critical eye too; the characters we see on our screens might be based on their performers, but they’re fundamentally fictional in all the ways that matter, and it’s probably healthier for all of us to view them that way.

Because just as “authentic” lifestyle trends promote the virtues of skincare on acne-free women and sell “unconventional” beauty trends on otherwise perfect faces, consumers of online media have proven time and time again that they don’t actually want authenticity, even when it is available to them. Influencers like Mikayla Nogueira, a makeup guru who faced inconceivable backlash when she complained about her career in a moment of unfiltered frustration, are frequently punished for sharing realistic (if unflattering) glimpses into their minds and lives. Yes, missteps like these are often out-of-touch or even insulting to the average viewer, but I often wonder if these influencers ever feel genuine confusion when the fans who beg them to share every thought, opinion, and private moment turn violent once they actually get what they’ve asked for.

In some cases, consumers can also build their own personas for celebrities or influencers who don’t do a good enough job of fulfilling their fantasies. Online, John Mulaney’s image was that of a wholesome cartoon character, defined by loving his wife and being “one of the good ones”. When his marriage ended amidst cheating rumours and stints in rehab, the fanbase that had declared him a queer and feminist icon felt personally betrayed, and erupted in fury. Even today, it’s not uncommon to see Mulaney’s name mentioned alongside abusers, groomers and sex offenders on lists of men who used a “good guy” persona to manipulate their audiences. The problem, though, is that Mulaney never endorsed or even contributed to the image that came to define how people consumed him: a couple jokes and offhand lines about liking his wife was enough for fans to build an idealised version of him that shared little in common with reality (his stories about being a drug addict with a complex past went strangely unrecognised by his online fanbase). When he got divorced, fans saw his real self clash with the fictionalised Mulaney that they’d invented; and many placed the blame squarely on his shoulders.

In both examples, authenticity is most comfortable as an illusion. When famous personalities like Mikayla Nogueira or John Mulaney do present themselves realistically, it’s either ignored (in service of imagining a more convenient character) or punished (for conflicting with the person that consumers want them to be). Perhaps even more frequently, creators respond to the public’s desires by crafting a persona based in moral perfection, aesthetic progressivism or kitschy “wholesomeness”, often in contrast to their real-life behaviour. I think these endeavours can be so successful, in part, because the public wants to believe that they’re real. After Ned Fulmer’s cheating scandal was made public, ex-fans unleashed a landslide of viral videos analysing his past behaviour and exposing problematic moments — but if the signs had always been there, why didn’t they matter until now?

As people increasingly seem to define themselves by the media they consume, I wonder if we convince ourselves that creators have spotless personal lives and impossibly aligned moral compasses in an effort to feel like good people for engaging with them. Uncomplicated “good guys” and “bad guys” can only be found in the world of fiction, and it’s comforting to imagine a world where we can make consumption choices that are truly, simply good. I’ve often found myself craving morally simple media as the world around me gets increasingly complex; in a media landscape that incentivises performance of the self, perhaps some influencers are just endeavouring to give the public what they want.

This isn’t to shift responsibility from people who build public platforms that enable them to hurt people without consequence; that behaviour is inarguably reprehensible. You also, of course, don’t have to like it when a celebrity or influencer does something you disagree with. You can choose to stop consuming someone’s work at any time, for any reason. My point is just that a culture that itches to blur the lines between character and performer — to consume the lives of real people, while also rebuking their humanity — often serves to punish people for complexity and simultaneously protect those who do real harm. After all, how many times has the culture viewed a wholesome on-screen performance as proof that the creator could do no wrong?

Trying to accurately reflect the self onto a two-dimensional phone screen is impossible. We’re all playing characters: everyone is exaggerating parts of their personality, hiding flaws, trying to seem funnier or cooler or more aware than they actually are. The people who turn that character into a profitable brand are professional entertainers, and should be thought of as such. Perhaps in our hunger for authenticity (and the financial imperative to provide the facade of authenticity to us), we end up projecting more on to these influencers than they deserve. I don’t know if the world would be better if we viewed every vlogger as an actor playing a role on-screen, but I do think that we need to try and see the online world for what it is: a stage.

Trying to accurately reflect the self onto a two-dimensional phone screen is impossible. We’re all playing characters: everyone is exaggerating parts of their personality, hiding flaws, trying to seem funnier or cooler or more aware than they actually are. The people who turn that character into a profitable brand are professional entertainers, and should be thought of as such. Perhaps in our hunger for authenticity (and the financial imperative to provide the facade of authenticity to us), we end up projecting more on to these influencers than they deserve. I don’t know if the world would be better if we viewed every vlogger as an actor playing a role on-screen, but I do think that we need to try and see the online world for what it is: a stage.