The archive of this short-lived print magazine is online and it's the perfect place to get lost in.

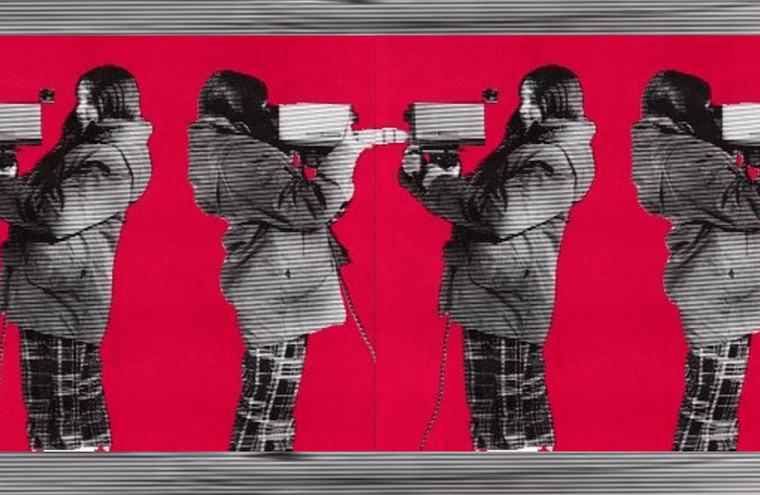

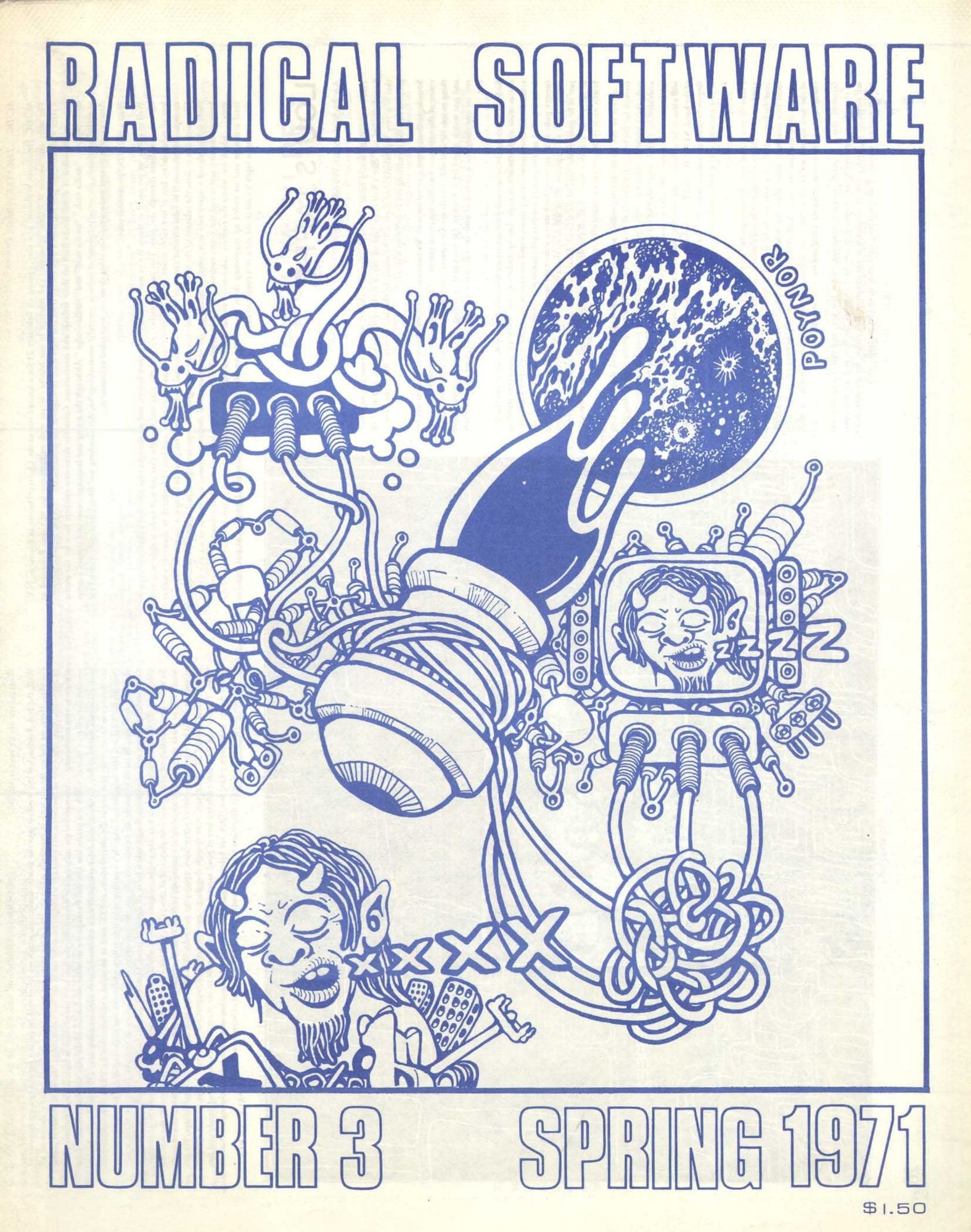

In the spring of 1970, a group of self-proclaimed “hardware freaks” published the first issue of Radical Software, a print magazine that detailed emerging trends in video, television, and early computing. Its pages burst with enthusiasm—there are guides for creating neighborhood documentaries, comedic recipes for “video rabbit,” and calls for new “information economies” meant to liberate data from private ownership. In an article for Rhizome, artist Phyllis Segura (then Gershuny, co-founder with Beryl Korot) writes, “the underlying circumstances that led to Radical Software… [were] curiosity and confinement.” Sound familiar?

In the long shadow of COVID’s second winter, I find myself returning to the magazine’s online archive, a retro website designed by Cory Arcangel (yes, that Cory Arcangel), Carol Parkinson, and Taketo Shimuda. Despite its short eleven-issue run, the reverberations of the magazine’s lively, provocative ideas are deeply felt. The magazine was immediately popular upon its release, honing in on a nascent desire to resist the status quo of broadcast television and military-funded computer development. Radical Software chronicles a unique moment in media history before the rise of personal computing and e-commerce, an exploratory set of texts that can inspire even the most jaded doomscroller.

The artists and writers of Radical Software were especially interested in cybernetics, a school of thought that focused on the increasingly porous boundaries between humans and machines, igniting the potential for radical new social orders. In the 1960s and ’70s, through the use of feedback loops and information processing, technology could adapt to and predict behavior in real-time. We know this kind of artificial intelligence as “the algorithm,” the thing that feeds you Cuup bra ads and @addisonre dance videos after tracking what you watch and “like.” But before Instagram told us that creating a profile was a viable means of “self-expression”—and not just a way to know if we liked Outdoor Voices—this budding technology was an opportunity to disrupt the powers that be. For Radical Software media-heads, early A.I. embodied the collision of people and machines, presenting an opportunity for what scholar Carolyn Kane calls “a liberation from Occidental notions of autonomy and selfhood.” By using software and video, Kane continues, people could “overcome” their limited individuality “through… collective, electronic circuits of connectivity.” The ideas explored in Radical Software circle the twin poles of cybernetics—video feedback and information processing—to break apart notions of the self in the digital age.

The possibility of freely accessible information and new, communal selves ignited New York City’s artistic community. Radical Software editors developed a unique symbol to capture their anti-privatization sentiment: an “x” inside a circle, explained in the first issue’s introduction as “the antithesis of the copyright—a symbol for “Xerox” that means ‘DO COPY!’” The people behind Radical Software believed in technology’s ability to expand the self, moving fragmented, postmodern subjects into new spaces defined by collective ownership. In “From Crucifixion to Cybernetic Acupuncture,” Paul Ryan writes, “videotape… allows one to think of [the] self not as a center on a private axis, but as part of a trial and error nexus of shifting information pathways.” Their ideas range from serious to playful, imagining an intimacy between humans and machines that could democratize information and shatter the constraints of the individual.

But logging on isn’t destroying the boundaries of my selfhood any more than a trip to the mall would. We are made increasingly aware of our “dependence” on the internet in a language redolent of that used to describe unhealthy relationships—we are overly reliant, isolated, and controlled. Under the contemporary moral compass, constant users are criticized for their addiction and “good” users applauded for limiting their Screen Time. What was radical to the 1970s artsy technophile—the total merging of people and machines—is now reflective of an omnipresent corporate superstructure, of the dominance of digital marketing and the privatized web. And rightfully so, as the accessibility of personal information became fodder for the corporate feed mill. The voluntary surrender of data now fuels the engine of social media and advertising—not the revolutionary ego death imagined by the founders of Radical Software.

Sort of. Like other millennial-zoomer cusps, my relationship to the internet started in late childhood, where online chat forums and distant networks (Club Penguin, Neopets, Omegle—for me, embarrassingly enough, a website for young writers called KidPub) allowed me to explore my identity and make connections with people I would never meet in “real life.” Maybe it’s this nostalgia for digital communities that draws me to Radical Software’s online form. The website design—stock sans-serif font, annoying pop-up windows, long walls of text—reminds me of the internet’s cowboy years, the 1990s, when webpages and blogs weren’t owned by a select few mega-corps. Even though my net world is long gone—bombed by Our Place pans and Shein dresses—I still want what it used to give me: escape, freedom, discovery. Of course, the writers and editors of Radical Software were acutely aware of the threats posed to their techno-optimism. Their conversations about predatory data usage and subversive human-machine selves stretch across time, reconciling relationships with technology that are both resentful—selling my preferences for profit, how dare you!—and intimate, a moving, breathing part of contemporary experience.

As Korot and Segura write in the magazine’s first issue: “Our species will survive neither by totally rejecting nor unconditionally embracing technology—but by humanizing it: by allowing people access to the informational tools they need to shape and reassert control over their lives.” Radical Software didn’t survive as a print publication—they shuttered in 1973 due to financial difficulties—but its second life feels almost more vibrant than its first. Reading through the website feels like getting lost in a comment thread on an obscure YouTube video, like talking to people shielded by usernames in some dark corner of Reddit. As we move (even more) online, Radical Software is a jolt for the cyber-soul, a panacea for the Zoom-fatigued. At its best, it feels like what the internet should be: overflowing and alive, anonymous and free.

Source: Garage

Follow OK Mag on, Instagram for more news.